The “Carbon Dioxide Problem”: Nixon’s Inner Circle Debates the Climate Crisis

On the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970, President Nixon and First Lady Pat Nixon plant a California Giant Sequoia tree on the South Lawn (Nixon Foundation, WHPO-6308-10A)

Nixon Science Adviser: Become “Snow-Tripping Mastodons” or “Grow Gills” to Survive Sea-Level Rise

Costs of Climate Study “Not Quantifiable” Since “Man’s Very Survival” at Stake

“Burning of Fossil Fuels” Main Cause of Growing “Instability”

Nixon Aides Called for Worldwide Climate Monitoring System

and International Cooperation on Environmental Issues

Published: Apr 26, 2024

Briefing Book #

858

Edited by Rachel Santarsiero

For more information, contact:

202-994-7000 or nsarchiv@gwu.edu

Subjects

Project

Climate Change Transparency Project

President Nixon visits Santa Barbara Beach in March 1969, two months after what was then the largest oil spill in U.S. waters. (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

President Nixon signs the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, January 1, 1970. [Nixon White House Photographs, 1/20/1969-8/9/1974; Collection RN-WHPO: White House Photo Office Collection (Nixon Administration); Richard Nixon Library, Yorba Linda, Ca. NAID 27580121]

President Nixon signed two pieces of legislation on April 3, 1970: The Water Quality Improvement Act (H.R. 4148) and a law that authorized the acquisition and improvement of land needed for the establishment of Point Reyes National Seashore (H.R. 3786). (Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, WHPO-3247-03)

High school students in Denver march on the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970. Environmental demonstrations were modeled on antiwar and civil rights protests. (The Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, RMN2129)

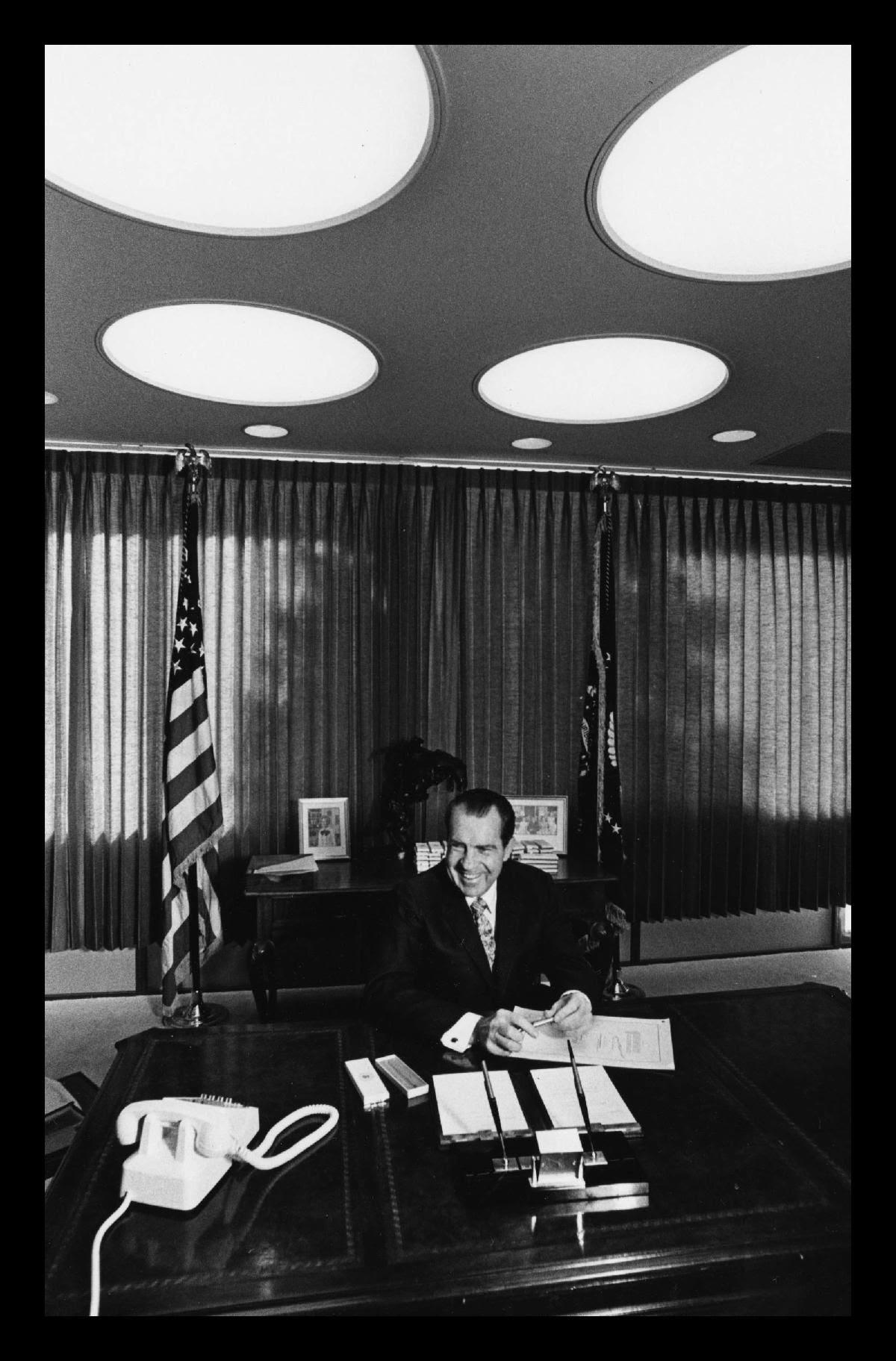

Nixon signs the Clean Air Act of 1970. Nixon is flanked by William Ruckelshaus, head of the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency (at left), and Russell Train, chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality (at right). (Associated Press)

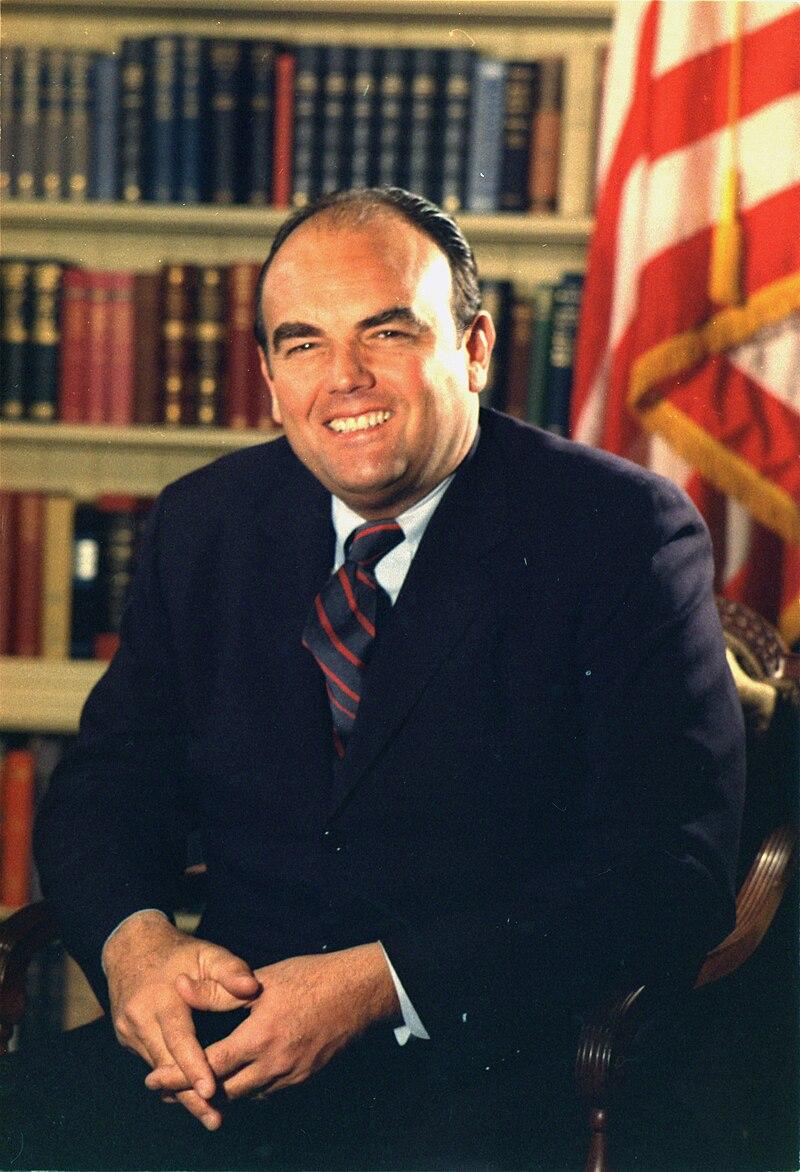

Staff portrait of John D. Ehrlichman, Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs. (Oliver F. Atkins, Photographer, NARA record: 8451334, NARA)

President Nixon and advisor Daniel Patrick Moynihan in 1970. (Associated Press)

Washington, D.C., April 26, 2024 – High-level officials inside the Nixon administration debated climate change and the impacts of sea-level rise, extreme temperatures, and fossil-fuel consumption as early as 1969, according to declassified documents posted today by the National Security Archive’s Climate Change Transparency Project.

To celebrate Earth Day, the National Security Archive this week publishes a small collection of records from the Nixon Presidential Library and other sources that shed light on the internal debates Nixon advisors were having about climate change and other environmental issues amid the rise of the American environmental movement of the 1970s. The records published here today include correspondence between Nixon aide Daniel Patrick Moynihan, domestic affairs adviser John Ehrlichman, and the Deputy Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Hubert Heffner, among others, and provide new details on what was a first-of-its-kind White House climatic assessment initiated in 1971.

The Climate Change Transparency Project seeks to uncover previously closed and classified documents that illuminate the policy debates and decisions that have guided the United States through more than 40 years of climate change negotiations and global environmental issues. Tracing the arc of the major diplomatic efforts of the 1970s and 1980s—including the most successful environmental treaty to date, the Montreal Protocol—a primary focus of the project is to document U.S. efforts to reach agreement on a treaty to curb greenhouse gas emissions driving global warming.

Combining hundreds of FOIA requests and open-source research, this project uses primary sources to track decades of U.S. debates around climate change and environmental diplomacy inside the White House, State Department, and other agencies—including the EPA, CIA, and the Defense, Commerce, and Treasury departments. This evidence-based approach augments the available scholarship on climate change by revealing how the debates evolved behind-the-scenes—from the establishment of key environmental agencies under Nixon, to the successes of the Montreal Protocol and the failures of the Kyoto Agreement, to the Paris Climate Accords and the present-day partisan discourse.

The Nixon-era documents posted today are a reminder that the policies and rhetoric of U.S. conservatives toward environmental issues have not always been as divisive and vitriolic as in recent years.[1] [2] On the one hand, Nixon was an unlikely environmental reformist, who was often disdainful of environmental activism. But Democrats and Republicans also found much common ground on environmental issues, and key officials in the Nixon White House were free to discuss and debate the origins and impacts of climate change and the implications for government policy without the level of polarization often seen today. As a result, President Nixon left a significant environmental legacy, fostering the passage of important legislation and the establishment of key agencies such as the EPA and CEQ.[3]

* * * * *

In his first State of the Union Address in 1970, President Nixon designated the environment as the defining issue of the decade: “The great question of the Seventies is … shall we make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water?”[4]

Although Nixon’s political conservatism fueled his election, the United States was entering a new age of environmental awareness during the 1960s and early 1970s. In part galvanized by the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 and Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb in 1969, and spurred by the largest-ever oil spill from an offshore rig in Santa Barbara that same year, the public was demanding increased environmental awareness from its leaders.

Recognizing the huge political power of environmentalism, the Nixon administration and Congress initiated many of the most important, and enduring, environmental policies in U.S. history, including:

- The signing of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1970

- The signing of the Clean Air Act of 1970

- The signing of the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1969 and the Endangered Species Act of 1973

- Establishing the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) in 1969

- Establishing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970

- Establishing the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 1970

By the time he had declared the first-ever Earth Day on April 22, 1970 (an environmental initiative originally proposed by Sen. Gaylord Nelson (D-WI) after the Santa Barbara oil spill), President Nixon had signed over ten pieces of major legislation on environmental issues and established key agencies that would become the bedrock of American environmentalism.

Despite his green record as president, Nixon was ambivalent, at best, and often derisive in his personal opinions about environmentalism. In a private meeting with Henry Ford II, Nixon said environmental predictions were “greatly exaggerated” and he blasted environmentalists for wanting humans to “go back and live like a bunch of damned animals.”[5] But his private fulminations about environmentalists did not seem to carry over into policymaking.

Instead, Nixon relied on his closest advisors to manage environmental policy. John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s domestic policy adviser, and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, one of a handful of Democrats to serve in the Nixon administration, were important influences on White House environmental initiatives. According to historian Joan Hoff, Nixon “turned the environmental policies over to Ehrlichman,” telling him to “keep me out of trouble on environmental issues,” while privately continuing to call the environmental movement “crap for clowns.”[6] He would also bring on “forceful environmentalists” William Ruckelshaus and Russell Train to run the EPA and CEQ, respectively, and John C. Whitaker, another key domestic affairs aide who in 1973 was appointed as Under Secretary of the Interior.[7]

Outside of the White House, Democratic senators, including Edmund Muskie (Hubert Humphrey’s running mate) and Henry “Scoop” Jackson, put pressure on Nixon to tighten environmental regulations. Both senators “created problems for the new president,” with Jackson aiming to coordinate the government’s environmental policy through the congressionally proposed CEQ, and Muskie proposing that oil companies be held fully liable for spills. Nixon complained to Ehrlichman about the “onslaught of Democratic proposals,” prompting environmentalists within the administration, like Train and Whitaker, to push Nixon to “act more assertively to claim [the environment] as a Republican issue.”[8]

Amid various environmental initiatives, Nixon’s advisors believed that global warming, specifically, was a “subject that the Administration ought to get involved with.” Seven months before the first Earth Day, Moynihan wrote to Ehrlichman warning of the potential dangers “of the carbon dioxide problem,” mentioning topics that persist in the discussion about climate change impacts today. These included extreme temperatures and sea-level rise, which he said would mean: “Goodbye New York. Goodbye Washington, for that matter.” Moynihan said that the “burning of fossil fuels” was one of the main causes of increased atmospheric “instability” and pressed for the creation of a worldwide system to monitor carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, something that would not become part of the public conversation on climate change for decades. (Document 1) At the end of the memo, Moynihan attached a 1965 report by the Environmental Pollution Panel of President Lyndon Johnon’s Science Advisory committee, which summarized the risks of rising carbon pollution. (Document 2)[9]

Several months later, Hubert Heffner, Deputy Director of the Nixon administration’s Office of Science and Technology, responded to Moynihan, acknowledging that atmospheric temperature rise was an issue that should be looked at. “The more I get into this, the more I find two classes of doom-sayers, with, of course, the silent majority in between,” he wrote. “One group says we will turn into snow-tripping mastodons because of the atmospheric dust and the other says we will have to grow gills to survive the increased ocean level due to temperature rise.” (Document 3)

Within the White House Office of Science and Technology, under the authority of Office Director Edward E. David, a sub-initiative was proposed to evaluate the impacts of “climate change caused by man and nature” and to create additional global baseline monitoring stations to “assess current and future impacts of natural climatic changes, provide alerts to potential catastrophic trends, and gain new environmental insight and understanding.” (Document 4) Similar to Moynihan’s first memo to Ehrlichman, the newly published sub-initiative outlined several topics that have particular relevance to today’s climatic discourse, including the linkage of land and air travel to air pollution and climate change to potential natural disasters. The authors observed that the benefits of one of the proposed “remote sensing” initiatives were “immense but not quantifiable since the element contributes to ensuring man’s survival.”

David would go on to join the oil and gas industry, serving as President of Exxon Research and Engineering (ER&E) from 1977 to 1986, during which time Exxon launched its own research into the release of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel combustion and the effects of these emissions on global climate. In 1979, David signed off on an Exxon project that used one of its oil tankers to track atmospheric and oceanic carbon dioxide samples and he also oversaw the company’s general climate modeling.[10] Oddly enough, David would later become a climate change denier and was one of 16 co-authors of a 2012 Wall Street Journal op-ed claiming that there was “no need to panic about global warming.”[11]

The Nixon administration’s domestic commitment to environmental progress gave credibility to U.S. leadership on the international stage, playing what CEQ Chairman Russell Train later characterized as “an active role on environmental issues in the principal multilateral institutions.”[12] Moynihan and Ehrlichman saw an opportunity for the United States to lead the global movement in combatting environmental problems, a vision outlined by Moynihan in a proposed policy directive for the Secretary of State. (Document 5) In it, Moynihan advocated for concentrating U.S. international efforts within three major organizations: NATO (which he proposes in Document 1), the United Nations, and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). According to a memorandum from Acting Secretary of State U. Alexis Johnson to President Nixon later that month (Document 6), Nixon approved the policy toward the “Major International Organizations Dealing with the Environment.”

While Train has noted that Nixon and principal foreign policy advisor Henry Kissinger never “assigned any significance to environmental concerns in any of their later foreign policy writings,” Nixon was still closely involved with the international environmental agenda, including efforts ahead of the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden.[13] The administration also pushed the OECD to adopt a “polluter pays” principle, a concept designed to promote free market mechanisms in addressing pollution. On the 20th anniversary of NATO in 1970, Nixon proposed that the alliance undertake a new non-military dimension that would become the Committee on the Challenges of a Modern Society (CCMS). (Document 7) The CCMS addressed various pollution problems and environmental management issues, as well as automobile safety and disaster relief.[14]

One of the most notable international environmental efforts, however, was the U.S.-USSR environmental agreement signed by Nixon at the Moscow Summit in June 1972. (Document 8) The agreement covered air pollution modeling, pesticides, conservation, preservation, and earthquake predictions. According to Train’s account of the agreement, “as many as 700 scientists and other environmental professionals participated annually in the exchange program,” making it one of “the most comprehensive, bilateral, and environmental agreement[s] ever attempted.”[15]

Today, Nixon’s environmental achievements tend to be overshadowed by discussions of his overall record as President. However, the documents posted below demonstrate that the administration’s environmental agenda began to answer the call from American environmentalists and established credibility on the international stage as the United States became a world leader in environmental protection programs. Bipartisan support for environmental issues in the Senate undoubtedly played a major role in the success of the administration’s legislative agenda, and Nixon’s personal disdain for environmentalism and environmentalists at times seemed in marked contrast to his administration’s overall efforts. Despite this, his time in office marked a moment when environmental issues were at the forefront of the political agenda and could be discussed without the virulent discourse of today’s climate debates.

THE DOCUMENTS

Document 1

Sep 17, 1969

Source

Nixon Presidential Library

Daniel Moynihan’s fascinating and frequently cited memorandum to John Ehrlichman begins with the question of the “carbon dioxide problem.” Moynihan, Nixon’s Executive Secretary of the Council of Urban Affairs and a sociologist believes that increased levels of CO2 in the atmosphere “very clearly is a problem” and that the scale of such impacts would “seize the imagination of persons normally indifferent to projects of apocalyptic change.” As such, this is something Moynihan strongly believes “the Administration ought to be involved with.”

Interestingly, Moynihan also mentions “countervailing” practices humans could take to lessen the impacts of the CO2 effect, including the suggestion of geoengineering techniques that are often mentioned amid today’s myriad of “climate solutions.” Such efforts would have to be “fairly mammoth man-made efforts to countervail the CO2 rise.” Moynihan also urges the administration to initiate a worldwide system of monitoring carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and believes that NATO would be a suitable organization to deal with this international challenge, in part for its expertise in the field and experience with international research coordination. Moynihan attaches the 1965 White House Science Advisory Report to the memorandum (Document 2), and this is presumably from where he pulled the carbon dioxide statistics that appear in paragraph two. He also cites Dr. Hubert Heffner, the Deputy Director of the Office of Science and Technology, and Robert White, the head of the U.S. Weather Bureau, as resources to contact on this issue.

This famous memo is one of the earliest known warnings about climate change and atmospheric warming that circulated in the high levels of the U.S. government. While quotes and excerpts from the document have been published previously, the National Security Archive here posts the complete record as a vital archival resource.

Document 2

Nov 1, 1965

Source

University of California Libraries

This 1965 report by President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Science Advisory Committee warns about the impacts of pollution and humanity’s role in curbing its effects. The panel suggests “economic incentives to discourage pollution” in which “special taxes would be levied against polluters.” The selected excerpt posted today features Appendix Y4 on “Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide,” in which the panel’s chairman, Roger Revelle, and other climate scientists focus on the hazardous increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide due to humanity’s production and combustion of fossil fuels. Moynihan attached the “Conclusions and Findings” from this appendix to his September 17, 1969, memo to Ehrlichman (Document 1).

In Appendix Y4, the authors link the “measurable” effects of fossil fuel production to the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide. The Committee reports that fossil fuel combustion is the only new major producer of carbon dioxide, having increased the quantity of CO2 in the atmosphere and ocean from 1860 to 1960 by roughly 7%. Revelle and his co-authors pose two open questions: 1) “What will the total quantity of CO2 injected into the atmosphere (but only partly retained there) be at different future times?” and 2) “What would be the total amount of CO2 injected into the air if all recoverable reserves of fossil fuels were consumed?” Their answer follows: “At present rates of expansion in fossil fuel consumption, this condition could be approached within the next 150 years.”

Throughout this featured section, the authors predict a future of melting ice caps, rising sea levels, and acidification of water sources. They conclude with a warning of the effects to come: “By the year 2000 the increase in atmospheric CO2 will be close to 25%. This may be sufficient to produce measurable and perhaps marked changes in climate, and will almost certainly cause significant changes in the temperature and other properties of the stratosphere.”

Document 3

Jan 26, 1970

Source

Nixon Presidential Library

Four months after Moynihan’s September 17, 1969, memo (Document 1), comes this oft-cited document in which the Deputy Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology, Hubert Heffner, responds with his thoughts on the issue of carbon dioxide and atmospheric temperature rise. Heffner agrees that this is an issue that needs more attention: “The more I get into this, the more I find two classes of doom-sayers with, of course, the silent majority in between.” Some of the more extreme solutions suggested by Heffner, such as “snow-tripping mastodons” and “growing gills,” sound like science fiction. To Heffner and others, the potential consequences of climate change were “so large” but were still based on theoretical hypotheses and were for future generations to address. Even so, to Heffner, it is still important to “find out what the true situation is.” He writes that he will ask the Environmental Science Services Administration to look further into the issue and says he will bring up the issue at an upcoming engineering conference, but there is no record indicating whether or not either of these follow-ups occurred.

Document 4

Dec 20, 1971

Source

Nixon Presidential Library

This newly published record details some elements of the New Technology Opportunities (NTO) program that was initiated by the Office of Science and Technology to stimulate research and development toward the application of new technology to national problems, including energy, the environment, health care, natural disasters, and transportation. On pages 1 and 2, the sub-initiative entitled “Determine the Climate Change Caused by Man and Nature” aims to “assess the future impact of natural climatic changes, provide alerts to potential catastrophic trends and gain new environmental insight and understanding as a basis for wise strategies.” This report notably links climate change “to all other initiatives to a varying degree,” such as the transportation industry, natural disasters, and human health. Pages 3-6 outline two program elements that are “essential for assessment of global climatic trends”: 1) to establish international and regional carbon dioxide monitoring stations, and 2) to use laser and other technologies for remote sensing to aid other climate modeling research. This report details the potential economic and social impacts of such an assessment, citing “immense” but “not quantifiable” benefits to “man’s very survival.”

Document 5

Aug 13, 1970

Source

Nixon Presidential Library

In a memo to Ehrlichman, Moynihan attaches a proposed draft memo on international environmental issues that he would like President Nixon to send as a directive to the Secretary of State. Moynihan proposes that the President set forth a “balanced and realistic” approach that Nixon “should lay down as law with respect to international environmental activities.” Moynihan’s draft memo calls for U.S. leadership on environmental issues at NATO, the United Nations, and the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), noting each institution’s expertise in environmental issues and their ability to galvanize international cooperation, specifically among “less developed countries” and “non-Communist industrial powers.” Moynihan’s memo also suggests that the U.S. increase its expertise in areas like regional land use planning, population distribution, and urban planning. The policy, in Moynihan’s view, would position the United States as a global leader on environmental issues while also leaning on the capabilities of these international institutions to “have a genuine impact on seizing environmental issues.”

Document 6

Aug 24, 1970

Source

National Archives, RG 59, Central Files 1970-73, SCI 41

Eleven days after Moynihan sent a memo to Ehrlichman about his idea for the administration’s involvement with international environmental issues (Document 5), acting Secretary of State U. Alexis Johnson sent this memo to President Nixon on a proposed new U.S. policy toward the major international organizations dealing with the environment: the United Nations, NATO, and OECD. In addition to recommending that the U.S. exercise “affirmative leadership” in each of the three organizations, Johnson also recommends that the United States “Encourage each organization to develop its special competences to the fullest.” A notation at the top of the first page indicates that President Nixon approved the statement.

Document 7

Jul 1, 1970

Source

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Kissinger Papers, Box CL 6

In this 1970 memo to President Nixon, Moynihan provides a report about the NATO Committee on the Challenges of Modern Society (CCMS). The CCMS was an initiative originally proposed by Nixon to focus on common environmental problems in developed nations, with Moynihan calling the organization “the most active, and productive international activity of its kind.” He goes on to praise the participation of other countries, including the Netherlands, Germany, Britain, France, Belgium, and Canada, although he remarks about a few “rather inactive” nations including Norway, Denmark, and Iceland. The CCMS tackles a range of projects related to air pollution, disaster assistance, traffic safety, sea pollution, inland water pollution, and narcotics. Moynihan concludes that the CCMS has grown “a long way from [its] shaky beginning,” but its longevity will still require “an expression of interest” by Nixon, especially to the other participating countries.

Document 8

Dec 1, 1971

Source

Digital National Security Archive, Presidential Decision Directives, Part II

The United States and the Soviet Union signed the Environmental Protection Agreement on May 23, 1972. Negotiated by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), the agreement included eleven specific areas of implementation covering various aspects of pollution and the environment. In this memorandum from five months earlier, during the negotiating stages, Kissinger tells Train, the chairman of the CEQ, that President Nixon has approved Train’s recommendations on environmental cooperation with the Soviet Union. Nixon has also “authorized” Train to “explore the possibility of conducting bilateral negotiations with the Soviets with the objective of producing a draft bilateral understanding that he might act upon during his May visit.” This record shows Nixon’s proximity and involvement with the U.S.-USSR environmental agenda, given his “wish to review [Train’s] report and recommendations” after the exploratory talks. Unwilling to fully commit to a bilateral agreement with the Soviet Union at that time, however, Nixon has directed that “no environmental agreement with the Soviet Union be initiated or otherwise concluded without his approval.”

NOTES

[1] Mark Joyella, “On Fox, Donald Trump Calls Climate Change A ‘Hoax’: ‘In the 1920’s They Were Talking About Global Freezing’,” Forbes, March 21, 2022.

[2] For more information about the Republican Party’s environmental stances in 1968, see the August 5, 1968, Republic Party Platform. The statement calls for an expansion of urban green spaces and natural parks, declaring that “our nation must pursue its activities in harmony with the environment… We must be mindful of our priceless heritage of natural beauty.”

[3] See Joan Hoff’s, Nixon Reconsidered, for an analysis of Nixon’s innovative domestic policy reforms in welfare, civil rights, economic and environmental policy, and reorganization of the federal bureaucracy.

[4] President Nixon, “Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union,” January 22, 1970.

[5] “Nixon & Detroit: Inside the Oval Office,” Frontline, February 21, 2002.

[6] See Elizabeth Drew, Richard M. Nixon (The American Presidents), Series: The 37th President, 1969-1974, March 29, 2007.

[7] See Joan Hoff’s, Nixon Reconsidered, and Melvin Small’s, The Presidency of Richard Nixon (American Presidency Series), 1999.

[8] Meir Rinde, “Richard Nixon and the Rise of American Environmentalists,” Distillations Magazine, Smithsonian History Institute Museum & Library, June 2, 2017.

[9] The 1969 Moynihan memo to Ehrlichman first received major media attention in 2010 when the Nixon Presidential Library publicized 100,000 pages of presidential records. Since then, the document and excerpts from the record have been widely shared. The document recently resurfaced earlier this month, demonstrating its relevance to modern day climate problems.

[10] “Edward E. David,” Inside Climate News, September 15, 2015.

[11] “No Need to Panic About Global Warming” Wall Street Journal, January 27, 2012. This op-ed, signed by 16 scientists, lists reasons that politicians should not focus their efforts on climate change mitigation. The authors claim that a consensus hadn’t yet been reached on whether climate change was really occurring and stated that increased CO2 in the atmosphere may even prove beneficial for the planet, which has been widely disproven.

[12] See Russel E. Train, “The Environmental Record of the Nixon Administration,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, Winter, 1996, Vol. 26, No. 1, The Nixon Presidency (Winter, 1996), 194.

[13] For more information on the 1972 U.N. Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment, see National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book, “50 Years of U.S. Resistance to Environmental Reparations.” See also Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976, Volume E-1, Documents on Global Issues, 1969-1972, International Environmental Policy.

[14] Train, 194.

[15] Train, 195.